Capturing AI's value

LoRA without regret, and RL environments versus RL-as-a-Service

Note: From the next section onward, I explain all machine learning terms like “LoRA” and “full fine-tuning” assuming no background. If you prefer to focus on LoRA’s implications for AI value capture and decentralization, please watch the short NotebookLM-generated video summary of “LoRA Without Regret” just after the introduction and then jump ahead to the section titled “Tinker,” about two-thirds of the way down.

Introduction

On September 29, 2025, John Schulman and colleagues at Thinking Machines Lab published “LoRA Without Regret.” The research post addressed an enduring worry about low-rank adaptation (LoRA): does it match traditional full fine-tuning, or is it just a cheaper compromise? They showed that, configured correctly, LoRA matches full fine-tuning completely.

Thinking Machines Lab (colloquially “Thinky”) was founded in February 2025 by Mira Murati, formerly OpenAI’s CTO. John Schulman, OpenAI co-founder and former head of its reinforcement learning (RL) team, joined as Chief Scientist. Barret Zoph, who led post-training research at OpenAI, joined as CTO. About thirty researchers soon followed from OpenAI, Meta, and Mistral. The company is now reportedly in talks to raise a new round at a roughly $50 billion valuation, up from $12 billion in July. LoRA sits at the center of their business model.

In the following, I explain “LoRA Without Regret” in some detail. LoRA matters for the question of AI centralization: will a few AI labs control all specialized AI capabilities, or will companies be able to develop and retain their own? LoRA we can trust creates paths where businesses might own their AI advantages.

I also notice two contrasting approaches to commercializing post-training: companies that make RL environments versus those that offer RL as a service (RLaaS). Previously, I explained why the return of reinforcement learning portends labor automation, especially as we build technology that automates rather than augments human workers. The environments versus RLaaS distinction adds nuance about who controls the automation and captures AI’s financial value.

NotebookLM overview of “LoRA Without Regret”

Post-training

Foundation models such as ChatGPT and Claude are pretrained on enormous text corpora. Pretraining gives the model broad linguistic fluency and general reasoning ability—a kind of wide, general education, not tailored to any one purpose. Post-training is the next stage, where this general model is adapted into something useful, making it helpful, honest, harmless, or aligned to specific tasks. Post-training combines two core techniques:

Supervised fine-tuning (SFT) shows the model examples of good behavior, such as a well-structured legal memo or correct code for a task. The model learns by imitating labeled examples, getting feedback at every step as it predicts each next token (a small chunk of text, like a word or part of a word) and compares it to what should come next.

Reinforcement learning (RL) has the model try things, get scored, and learn what worked. The model generates a complete response (maybe thousands of tokens!) and receives just one reward signal at the end, telling it how well it did. The model has to figure out which earlier choices led to that outcome. The reward can come from human raters (reinforcement learning from human feedback, or RLHF) or from other models (reinforcement learning from AI feedback, or RLAIF).

Finally, a layer of safety tuning adds rules, refusals, and guardrails to shape what the model is and isn’t allowed to do.

In practice, AI labs mix and repeat these steps rather than running them in a fixed sequence. And as models shift from chatbots to agents, the fine-tuning stage is where they learn how to act inside workflows, not just how to speak inside conversations.

LoRA

Pretraining gives the model broad knowledge; post-training teaches it how to act. For AI applications, there is one more layer after that where the model learns specialized language, workflows, and domain habits. Many AI startups operate here. They are not training models from scratch, but wrapping base models (likely Qwen or another Chinese open-source model) and adding institutional flavor.

At first, this specialization step was done with full fine-tuning (FullFT): updating every parameter in the model based on a much smaller dataset (e.g., internal documents, annotated workflows, or examples of how a particular organization reasons). A parameter is a learned numerical weight—one of the tiny values that shape how the model behaves. At least for closed-source models, these weights are the core intellectual property of the AI lab.

But modern foundation models have over a trillion parameters. Updating all of them via full fine-tuning is extremely memory-intensive and expensive. Full fine-tuning needs the same number of GPUs as pretraining (albeit for a shorter time), which is often over ten times what serving the model requires. Only AI labs and very well-resourced organizations could afford to do it.

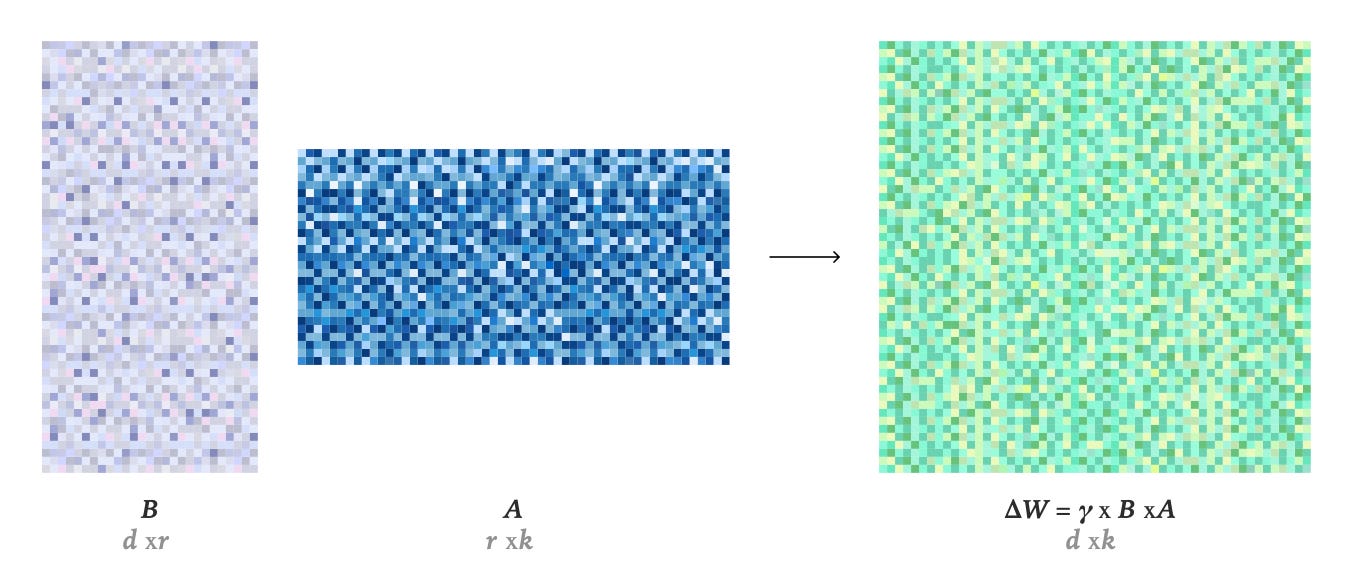

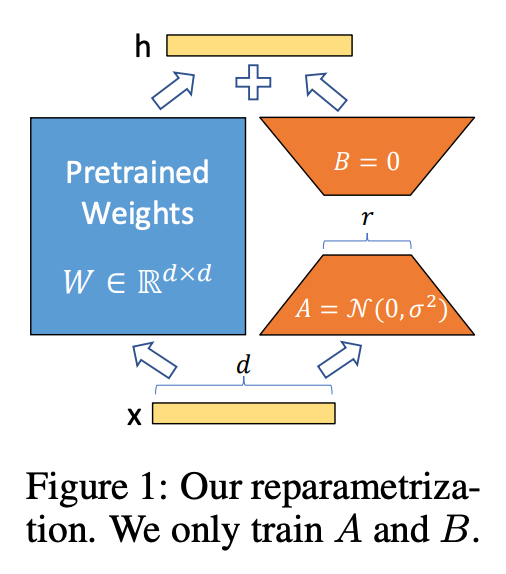

Parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods offer an alternative by training only a small number of new parameters. The leading PEFT method is low-rank adaptation (LoRA). Introduced by Edward Hu and colleagues in 2021, the technique freezes the base model’s original weights, then adds a correction on top of each weight matrix, based on two small trainable matrices B and A that are much smaller than the original weight matrix W. This correction is the LoRA update ΔW = γBA, illustrated below, where γ is a scaling factor. The modified weight matrix is W′ = W + ΔW.

By decomposing the weight update into this product of two low-rank matrices, LoRA reduces the number of trainable parameters drastically. The matrices B and A sit alongside the base model’s frozen weights, adding a correction. The base model has thousands of weight matrices across its layers; LoRA inserts these small corrections into many of them. Together, the corrections form an adapter, or the complete set of modifications that specializes the model for a specific task.

The funnel diagram from the original LoRA paper illustrates the computational flow. When an input x passes through the model, it takes two parallel paths: through the frozen pretrained weights W (the blue box) and through the low-rank adaptation BA (the orange funnel). While W is a d×d matrix with potentially billions of parameters, the adaptation narrows down through rank r, which might be as small as 1 or as large as 512. This bottleneck is what makes the adaptation “low-rank.” Matrix B starts at zero while A starts with small random values (as is standard in machine learning). Since B is zero, the product BA initially contributes nothing—the model behaves exactly like the original. During training, B and A update so that BA adds task-specific corrections to the pretrained weights. The outputs from both paths are summed to produce h, the layer’s output.

Rank refers to each correction’s internal dimensionality. Higher ranks allow more expressive adaptations but require more parameters. LoRA typically adds about 1% of the model’s original parameters, which still amounts to millions of parameters but remains a small fraction of the billions or trillions in the base model.

Rank determines capacity, or how much information each adapter can store. The question is whether this capacity is enough to achieve the needed capability, or the model’s final performance.

LoRA adapters are tiny compared to the base model, often hundreds of times smaller. This small size makes everything cheaper: one base model can keep many adapters in memory at once, adapter files are manageable to store and transfer, and training happens on the same hardware used to run the model.

Remarkably, LoRA very often exactly or almost exactly matches the performance of full fine-tuning at adapting the model to tasks. Schulman and colleagues at Thinking Machines demonstrated this equivalence systematically and identified the precise recipe for achieving it.

LoRA on SFT and RL

Schulman and colleagues compared LoRA to full fine-tuning across both post-training techniques described above: supervised fine-tuning and reinforcement learning.

SFT

For supervised fine-tuning, they ran experiments across model sizes and datasets, sweeping through different LoRA ranks from 1 to 512. They wanted to see exactly when and how capacity limits appear.

These graphs show four experiments. Llama 3.1 8B and Llama 3.2 1B are Meta’s language models with 8 billion and 1 billion parameters, respectively. Tulu3 and OpenThoughts are post-training datasets that are much smaller than pretraining data. Tulu3 teaches general instruction following like answering questions and writing emails, while OpenThoughts teaches reasoning tasks like solving problems step-by-step.

The vertical axis shows Test NLL, or negative log-likelihood, which measures prediction error. Prediction error is how wrong the model’s guesses are, so lower numbers mean better performance.

The horizontal axis shows training steps on a logarithmic scale (10², 10³, 10⁴ means 100, 1,000, 10,000 steps). At each step, the model processes a batch of training examples, often 32 or 64 at once, and updates its weights based on what it learned. So by step 1,000, the model has seen tens of thousands of individual examples.

Each colored line represents a different setup. The orange line labeled “full” is traditional full fine-tuning. All other lines are LoRA with different ranks, from 1 to 512. For scale: a rank-256 LoRA adapter on the 8B Llama model uses about 700 million parameters, which is less than 9% of the base model’s size.

We see that high-rank LoRAs (256, 512) track almost identically with full fine-tuning! They learn at the same rate and reach the same performance. Lower-rank LoRAs start on the same trajectory but gradually diverge. Rank-1 peels away first, then rank-2, then rank-4. The divergence point shows when that adapter runs out of capacity.

The pattern holds across all four experiments. For typical enterprise post-training datasets, LoRA’s capacity is plenty! The graphs show that picking a high enough rank is all that matters. Limits only become unavoidable when teaching the model massive amounts of entirely new information, which would be something closer to pretraining from scratch.

RL

They ran similar experiments for reinforcement learning, sweeping through different LoRA ranks and learning rates. For RL, the results are even more favorable to LoRA. Even rank-1 LoRA matches full fine-tuning performance for RL when properly configured.

The researchers switched to math datasets because RL needs clear feedback: right or wrong. MATH contains challenging competition problems, GSM8K has grade-school problems. As I explained in a previous post (see section “What is RL?”), reinforcement learning solves the problem of learning from sparse rewards. Unlike in supervised fine-tuning where every token from every example provides feedback, models trained with RL get just one signal at the end: did the complete solution work or not?

Notice the axes have changed from the SFT graphs. The vertical axis now shows final reward, or the model’s accuracy after full training, rather than prediction error during training.

The horizontal axis shows learning rate. Learning rate controls how fast the model moves through parameter space, or how much it adjusts its weights after each batch of problems. A learning rate of 10⁻⁴ means bigger steps than 10⁻⁵, which means bigger steps than 10⁻⁶, and so on.

The black curve is full fine-tuning, while the colored curves represent different LoRA ranks. All the curves peak at roughly the same height, achieving the same final performance. Even rank-1!

While rank-1 would quickly run out of capacity in supervised fine-tuning, for RL it works perfectly. This is because RL provides extremely sparse feedback, at most 1 bit of information per problem attempt (correct or incorrect), and often much less if the model already had high confidence in the outcome. Even after hundreds of thousands of attempts, the total information absorbed remains tiny. Meanwhile, rank-1 LoRA still totals about 3 million parameters—far more capacity than this sparse signal requires.

They validated this result on other datasets with the same finding: rank does not matter for RL. Both LoRA and full fine-tuning developed identical reasoning behaviors during training.

But getting these results requires configuring LoRA correctly. The black curve (full fine-tuning) peaks at a different learning rate than the LoRA curves. This is one of several factors that matter for getting LoRA right.

LoRA recipe!

Schulman’s team identified three factors that make LoRA match full fine-tuning.

1. Use 10x higher learning rate.

The black curve peaked at a different spot because LoRA consistently needs a learning rate about 10 times higher than full fine-tuning. Schulman’s team confirmed this across 14 different models, various dataset sizes, and both Llama and Qwen architectures. If full fine-tuning works best at 0.0001, start with 0.001 for LoRA. The theoretical explanation remains incomplete, but the empirical finding is robust and gives practitioners a reliable starting point.

2. Choose sufficient rank.

As we saw in the graphs earlier, rank requirements depend on the fine-tuning approach. For supervised fine-tuning on typical post-training datasets, rank-256 or rank-512 reliably matches full fine-tuning. For reinforcement learning, even rank-1 suffices because the minimal information requirements mean capacity is never the limiting factor.

3. Apply LoRA to all layers.

The original LoRA paper recommended applying adapters only to the attention weight matrices in the transformer, and many practitioners followed this guidance. But this was wrong.

Modern language models use the transformer architecture, which processes text through two main types of layers. Attention layers figure out which words in a sentence should interact with each other, like connecting pronouns to their antecedents or linking adjectives to the nouns they modify. MLP layers (multi-layer perceptrons, which are just stacks of mathematical transformations) process the information that attention has gathered. We can think of attention as selecting what to focus on, and MLPs as doing the actual computation with that information. The MLP layers contain most of the model’s parameters.

Schulman’s team tested applying LoRA to different layers and found that attention-only significantly underperformed, even at high ranks. Without modifying the computational layers, changing only attention patterns is not enough for the model to fully adapt. MLP-only LoRA worked well, but applying LoRA to all layers worked best.

Following this recipe, LoRA reaches parity with traditional full fine-tuning.

Tinker

Two days after the LoRA research post, Thinking Machines launched its first product: Tinker.

Tinker lets researchers and businesses fine-tune open-source models on their own data. Clients write training code and send both the code and their data to Thinking Machines’ servers for processing. Thinking Machines promises the data is used solely for training that client’s adapter, not for their own models (but you need to trust them on this point). After training, clients download their adapter and can use it anywhere. Thinking Machines handles the GPU infrastructure, but the client owns the adapter.

Early users have mostly been academic teams: Princeton’s Goedel Team trained models to prove mathematical theorems. Stanford’s chemistry group trained models on chemical reasoning. Berkeley’s SkyRL group ran reinforcement learning experiments with multiple AI agents learning to use tools together. Redwood Research used RL to train a model on AI safety tasks.

Tinker uses LoRA exclusively.

RL environments versus RLaaS

This technical advance enables a particular business model that has implications for who controls AI. Thinking Machines Lab represents one side of a fundamental split in how post-training gets commercialized.

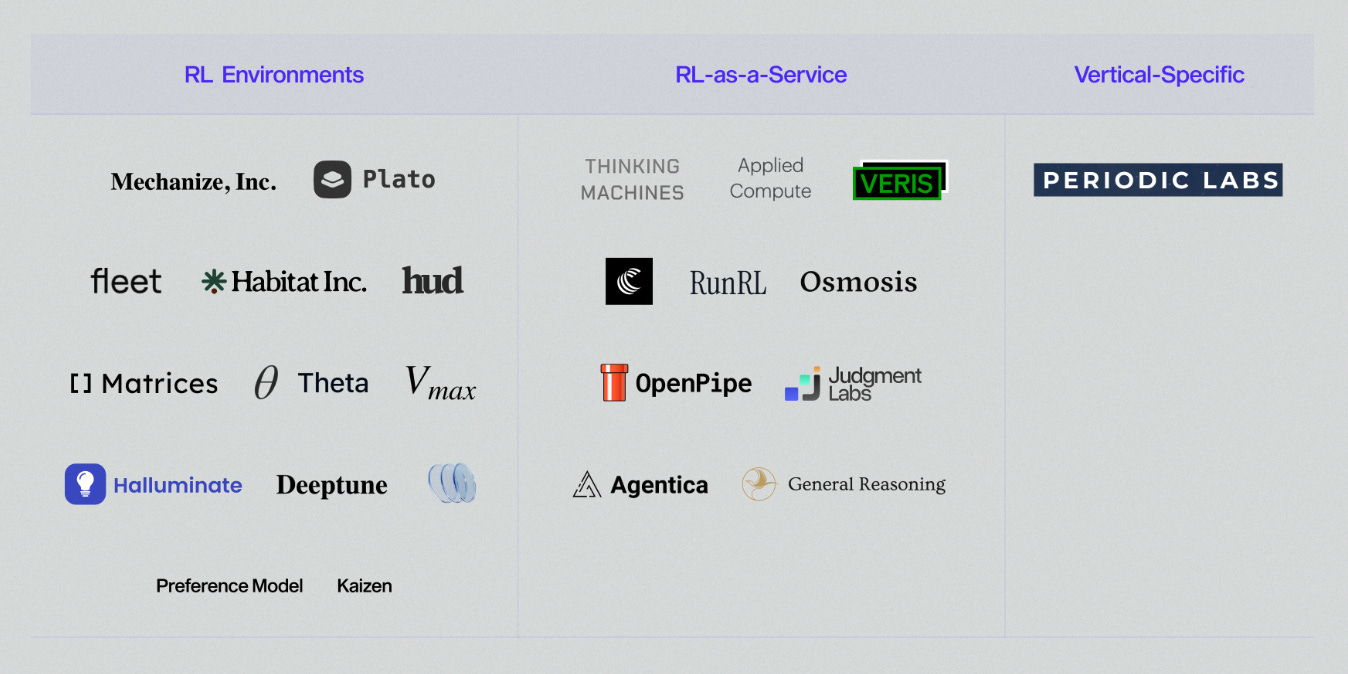

As I noted in a previous post (see section “A brief history of RL”), reinforcement learning on top of pretrained transformers is the current technical path from language models to automating knowledge work. In the diagram above, Ivory Tang from venture capital firm Chemistry identifies three kinds of RL companies. Environment builders create work simulations and sell them to AI labs. RL-as-a-Service (RLaaS) providers let enterprises train their own AI on their own data and workflows. Vertical-specific companies apply RL to specialized domains like drug discovery or materials science. The third category remains niche, so the real battle is between the first two.

RL environment builders construct full work simulations that replicate end-to-end white-collar workflows, where AI agents learn to perform remote jobs. Companies like Mechanize—currently focused on automating software engineering—sell these environments to AI labs, which also develop internal versions. OpenAI’s Project Mercury, for instance, pays ex-bankers $150 an hour to build financial models for IPOs and restructurings so agents can learn investment banking work. Once an agent is trained, the lab owns that capability indefinitely and can sell digital workers to every bank or compete directly.

RLaaS providers like Thinking Machines Lab offer training infrastructure directly to enterprises. For instance, Goldman Sachs could bring their own deal data and workflows to create customized AI. The training happens on the RLaaS provider’s servers, but Goldman owns the resulting adapter. The institutional knowledge stays with businesses.

LoRA makes the RLaaS business model viable by delivering cheap, high-quality fine-tuning. Thinking Machines Lab’s thorough hyperparameter sweeps made LoRA more reliable to deploy.

The Case for RLaaS

Compared to environment builders selling to labs, I am more excited about RLaaS. It keeps AI capabilities and power decentralized, letting individual enterprises capture value rather than watching AI labs absorb entire industries.

Digital workers (and later physical ones, with robotics progress) operate 24/7 without getting tired or demanding benefits, can be copied infinitely once trained, and cost only the compute to run them. Once digital workers are realized and compute becomes cheaper than human labor, AI labs that supply them may come to dominate every sector.

Back in 2019, three and a half years before ChatGPT’s launch, Sam Altman said in an interview that if OpenAI succeeds in building artificial general intelligence, it could “maybe capture the light cone of all future value in the universe.” In physics, a light cone describes all possible futures reachable from a single point in spacetime, so he was gesturing at the possibility of capturing the gains from all future productive activity anywhere in the universe. Today, OpenAI continues to define AGI in economic terms: “highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work.” Such concentration would make it nearly impossible for firms to compete or displace incumbents.

Yet, even as labs hire finance contractors and environment builders rush to simulate industry workflows, organizations have decades of institutional memory, proprietary methods, and context that outsiders may struggle to replicate. This specialized knowledge is what differentiates one company from another, and RLaaS might preserve that competitive differentiation.

True ownership of AI capabilities remains complicated, though. Enterprises own their adapters but still depend on external providers for the base model (except in the case of open-weights base models), compute, and the training infrastructure. They must trust that RLaaS providers will not share their proprietary data with labs or competitors. At least the specialized knowledge stays with the enterprise and powers their own custom digital workers.

Capturing AI’s value

For the average worker, the RL environments versus RLaaS distinction seems irrelevant at first. Whether you are automated by OpenAI or by Goldman Sachs, you are still automated.

But it matters enormously for the opportunity to capture value. Thanks to public markets, anyone can own stock in the companies driving automation. The problem is that AGI labs, especially the ones most likely to win the scaling race, are not publicly traded. Ordinary people are locked out of the steepest part of AI’s value curve. RLaaS changes this by keeping value from AI deployment in public markets. When enterprises create their own adapters, value stays with companies and shareholders rather than concentrating in private labs.

Of course, automation will arrive in waves rather than all at once. Current AI systems complement rather than substitute for humans (think of how much input you provide in every chatbot interaction!). Enormous value will flow to AI infrastructure and applications, creating new roles—for a time. Perhaps blue-collar roles will expand, given Moravec’s paradox. College graduates will likely face disappointment as promised white-collar career paths contract. There has never been a better time to start a company.

The economic incentives for automation are compelling, and lab leaders, investors, and engineers are racing to scale the intelligence and perfect the RL environments. In a world where base models and compute are controlled by a few providers, owning your data and fine-tuned adapters might be the most important leverage anyone retains.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Rebecca Lowe for detailed comments on definitions and clarity, to Rudolf Laine for fine-grained feedback on fine-tuning and AI power concentration, and to Liya Palagashvili for useful conversations about labor and entrepreneurship.

Couldn't agree more; your clarity on LoRA's implications for AI decentralization is truly spot on and so necesary.